-

Chinese culture

-

- A Company of Pilgrims(香会)《朝拜者连》

- Animal Path(畜生道)

- Begging for Alms(化缘)

- Buddha Position(佛位)

- Buddha Power(佛力)

- Buddha's Hand(佛手)

- Buddhism(佛教)

- Burn High Incense(烧高香)

- Cause and Effect(因果)

- Debating the Scriptures(辩经)

- Dharma Eye(法眼)

- Dharmakaya(法相)

- Eightfold Path of the Celestial Dragons(天龙八部)

- Enlightenment(正果)

- Golden Body(金身)

- Great Sage National Preceptor Wang Bodhisattva(大圣国师王菩萨)

- Head-Touch Ordination(摩顶受戒)

- Heavenly Eye(天眼)

- Immobilization Spell(定身术)

- Incense(香火)

- Kasaya(袈裟)

- Lotus Platform(莲花台)

- Magical Power(法力)

- Monastic Life(空门)

- Offer Sacrifice(供奉)

- Rakshasa(罗刹)

- Rakshasi(罗刹女)

- Red Boy(红孩儿)

- Ritual Implements(法器)

- Six Roots of Purity(六根清净)

- Spiritual Energy(灵气)

- Supernatural Powers(神通)

- Tathagata Buddha(如来佛祖)

- Wheel of Merits(功德轮)

- Yaksha(夜叉)

- Zen(禅)

- Show Remaining Articles (21) Collapse Articles

-

-

- Articles coming soon

-

- Articles coming soon

-

- Articles coming soon

-

- Articles coming soon

-

- Articles coming soon

-

- Articles coming soon

-

- Articles coming soon

-

- Articles coming soon

-

- Articles coming soon

-

- Articles coming soon

-

- Articles coming soon

-

- Articles coming soon

-

- Articles coming soon

-

- Articles coming soon

-

- Articles coming soon

-

- Articles coming soon

-

- Articles coming soon

-

- Articles coming soon

-

-

- Azure Dragon(青龙)

- Ba Xia(霸下)

- Bi An(狴犴)

- Black Tortoise(玄武)

- Celestial Beasts(仙兽)

- Chao Feng(嘲风)

- Chi Wen(螭吻)

- Chinese Zodiac(十二生肖)

- Fu Xi(负屃)

- Howling Celestial Hound(哮天犬)

- Pu Lao(蒲牢)

- QiLin(麒麟)

- Suan Ni(狻猊)

- Vermilion Bird(朱雀)

- White Tiger(白虎)

- Ya Zi(睚眦)

- Show Remaining Articles (1) Collapse Articles

-

- Alchemist(方士):

- Ashram(道场)

- Breath-Holding Talisman(闭气符)

- Breathing Exercises and Nurturing the Spirit(养神服气)

- Cultivation(修炼)

- Cultivator(修士)

- Dao Partner(道侣)

- Disciple(道童)

- Divination(算卦)

- Elixir(仙丹)

- Fortune-telling Stall(卦摊)

- Friar(修士)

- Fuban(蝜蝂)

- Golden Elixir(金丹)

- Heaven and Earth /Qian Kun(乾坤)

- Inner Elixir(内丹)

- Jade Emperor(玉帝)

- Kang-Jin Star(亢金星君)

- Magical Power(法力)

- Old Man of the South Pole(南极仙翁)

- Senior Sister(师姐)

- Spiritual Energy(灵气)

- Taibai Jinxing(太白金星)

- Taishang Laojun(太上老君)

- The Great Way(大道)

- True Martial Great Emperor(真武大帝)

- Tudigong Temples(土地庙)

- Tudigong(土地公)

- Twin Generals of Turtle and Snake(龟蛇二将)

- Yin-Yang Fish(阴阳鱼)

- Show Remaining Articles (15) Collapse Articles

-

- Banana Fan(芭蕉扇)

- Boshan Censer(博山炉)

- Divine Weapon(神兵)

- Eternity Pearl(定颜珠)

- Fire-protecting Cover(避火罩)

- Golden Cymbal(金铙)

- Golden Hairpin(金钗)

- Golden Hoop(金箍棒)

- Lord Lao's Furnace(八卦炉)

- Mace(狼牙棒)

- Qiu Niu(囚牛)

- Rake(耙)

- Root Instrument(根器)

- Samadhi True Fire(三昧真火)

- Species Bag(人种袋)

- The Lord of the Rings(魔戒)

- Vajra Cincture(金刚琢)

- Wisdom Pearl(慧珠)

- Show Remaining Articles (3) Collapse Articles

-

-

Humanities and Social Sciences

-

- Articles coming soon

-

- "Why is your head so pointy?"(你的头怎么尖尖的?)

- “Let me ask you this”(那我问你)

- Bullfighting Palace(斗牛宫)

- Cave of Fire Cloud(火云洞)

- Celestial Court(天庭)

- Celestial Ladder Kingdom(梯仙国)

- Dragon Palace(龙宫)

- Eastern Continent(东胜神洲)

- Flaming Mountains(火焰山)

- Flowing Sand Country(流沙国):

- Gao Lao Village(高老庄)

- Guaranteed(包的)

- Ling Tai Fang Cun Mountain(灵台方寸山)

- Martial Arts Techniques(功法):

- Minor Western Heaven(小西天)

- Mount Huaguo(花果山)

- Mount Luojia(洛迦山)

- Mount Wuxing(五行山)

- Northern Continent of Kuru(北俱芦洲)

- Paradise(极乐世界)

- Peach Banquet(蟠桃会)

- Purple Heaven Nation(朱紫国)

- River of Heaven(天河)

- Southern Heavenly Gate(南天门)

- The Three Realms(三界)

- Tightening Spell(紧箍咒)

- Today hot tip's:"You are truly famished"

- Tushita Palace(兜率宫)

- Vulture Peak(灵山/灵鹫山)

- West Liang Kingdom of Women(西梁女国)

- West(西方)

- Western Continent of Cattle-gift(西牛贺洲)

- Wusizang Nation(乌斯藏国)

- Yellow Flower Temple(黄花观)

- Yellow Wind Ridge(黄风岭)

- Ziyun Mountain(紫云山)

- Show Remaining Articles (21) Collapse Articles

-

Life, Art and Culture

-

- Articles coming soon

-

Nature and Natural Sciences

-

- Articles coming soon

-

Religion and Belief

-

- Bimawen(弼马温)

- Bodhisattva Lingji(灵吉菩萨)

- Bodhisattva Pilanpo(毗蓝婆菩萨)

- Bodhisattva(菩萨)

- Chang'e(嫦娥)

- Chen Loong(辰龙)

- Dawnstar(昂日星官):

- Erlang Shen(二郎神)

- Fairy(仙娥)

- Giant Spirit God(巨灵神)

- Jade Emperor(玉帝)

- Kang-Jin Loong(亢金龙)

- Kang-Jin Star(亢金星君)

- Li Jing(李靖)

- Maitreya Buddha(弥勒佛)

- Mountain God(山神):

- Nezha Third Lotus Prince(哪吒三太子)

- Queen Mother(王母)

- River God(河神)

- Seven Fairy Sisters(七仙女)

- Shen Monkey(申猴)

- Six Saints of Mount Mei(梅山六圣)

- Sudhana(善财童子)

- Taibai Jinxing(太白金星)

- Taishang Laojun(太上老君)

- Tathagata Buddha(如来佛祖)

- The Four Heavenly Kings(四大天王)

- The God of Wealth(财神)

- The Great Sage(齐天大圣)

- True Martial Great Emperor(真武大帝)

- Tudigong(土地公)

- Victorious Fighting Buddha(斗战圣佛)

- Xu Dog(戌狗)

- Yin Tiger(寅虎)

- Young Acolyte(童子)

- Show Remaining Articles (20) Collapse Articles

-

-

Society

-

- Articles coming soon

-

- "City不City": A Viral Phrase Explained

- "Job Aura"(班味): A Cultural Phenomenon in Modern Workplaces

- "Old Iron"(老铁)

- "Read and Reply Randomly"(已读乱回)

- "Squatting on something"(蹲一个)

- "Throwing in the towel" (摆烂)

- Bagua(八卦)

- Because He’s Kind(因为他善)

- Betrothal Gifts(彩礼)

- Breaking Down Defenses(破防)

- Brick Moving(搬砖)

- Chillaxation(松弛感)

- Coming Ashore(上岸)

- Contrarian Trolls(杠精)

- CPU你

- Crush

- Digital Pickles(电子榨菜)

- Enshrined in the Imperial Ancestral Temple(配享太庙)

- Eye-Catcher(显眼包)

- Getting soy sauce(打酱油)

- Grass-Stage Troupes(草台班子)

- Green Hat(绿帽子)

- Hard Control(硬控)

- Introverts person(i人):

- Involution(内卷)

- lemon envy/sour grapes(柠檬精)

- Lying flat(躺平)

- Mouthpiece(嘴替)

- Ocean King(海王)

- Princess, Please Get in the Car(公主请上车)

- Pure Love Warrior(纯爱战士)

- Red Heat(红温)

- Single Dog(单身狗)

- So What(那咋了)

- Social Butterfly

- Social Death(社死)

- Stealthy Sensibility(偷感)

- The Simp(舔狗):

- Versailles(凡尔赛)

- YYDS(永远的神)

- Show Remaining Articles (25) Collapse Articles

Gluten(面筋):

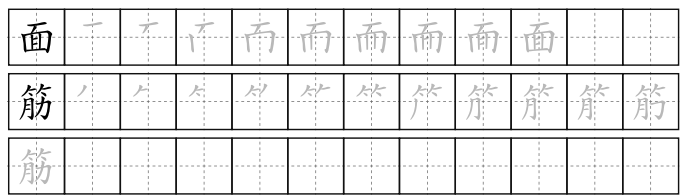

In Chinese, it is pronounced as: miàn jīn,Written as:

Gluten is a plant-based protein made up of gliadin and glutenin. To make gluten, flour is mixed with an appropriate amount of water and a little salt, stirred until it becomes tough, and then formed into a dough. The dough is then washed repeatedly with water to remove the starch and other impurities, leaving behind the gluten. To prepare fried gluten, it is shaped into balls and deep-fried in hot oil until golden brown, then removed and served. Boiled gluten is prepared by cooking the washed gluten in boiling water for 80 minutes until it is done, resulting in “water gluten.”

Historical records indicate that gluten was first created during the Northern and Southern Dynasties in China, and became a delicacy in vegetarian gardens, especially in dishes that mimic the taste and texture of meat, making it a unique aspect of Chinese cuisine that has been beloved for generations. By the Yuan Dynasty, gluten was produced in large quantities, and by the Ming Dynasty, Fang Yizhi’s “Little Knowledge of Physics” detailed the method for washing gluten. In the Qing Dynasty, the variety of gluten dishes increased, and new recipes were continuously invented.

Nutritionally, gluten is particularly high in protein, surpassing lean pork, chicken, eggs, and most soy products in protein content. It is a high-protein, low-fat, low-sugar, and low-calorie food, which also contains calcium, iron, phosphorus, potassium, and other trace elements, making it a traditional delicacy.

The origin of fried gluten can be traced back to a nunnery, where it was invented by a senior nun. The nunnery was located near the Five Mile Street Bridge, close to Huishan, and featured a serene environment. Throughout the year, devout Buddhists frequently visited, especially during festivals or on the birthdays of Bodhisattvas, with elderly women from Wuxi often staying to chant and meditate overnight, sometimes for as long as six or seven days. The nunnery’s cook, renowned for her vegetarian dishes, used raw gluten as the main ingredient in her cooking, creating dishes that were famous for their taste and variety, including braised, stir-fried, and soup-based dishes, often complemented with winter bamboo shoots and mushrooms, drawing praise from all who dined there.

Once, several elderly women from the countryside who had planned to come to the nunnery for an overnight prayer session failed to show up. The cook had already prepared several tables’ worth of raw gluten, which would spoil if left overnight. Concerned about the gluten spoiling, she first added some salt to the vat but remained worried. After some thought, she decided to try frying the gluten in oil to prevent it from going bad, ensuring it could still be used for cooking the next day. She heated a large amount of oil, and fearing that the gluten wouldn’t cook through, she fried small pieces at a time. As she tossed them in the oil, they expanded into golden, crispy hollow spheres. Scooped out and tested—crispy to the touch, fragrant to the nose, and delicious to the taste—the unanimous approval led to these fried gluten hollow spheres being named “oil gluten.”